The Shanghai event for Season II of “Our Water: Flowing from Shanghai—Intercultural Dialogues among World Cities” (referred to as Our Water) recently launched at the historic Shanghai General Chamber of Commerce on Suzhou Creek. With the season’s theme: “Open Waterfronts: Convergence, Co-creation, and Sharing”, it capitalizes on the city’s achievement of linking over 100 kilometers of waterfront pathways to reframe urban riverbanks as a new frontier for innovation and civilizational dialogue, moving beyond their traditional role as scenic backdrops.

Lou Yongqi, President of SUES and Honorary Doctor of the Royal College of Art, delivered a keynote speech titled Human-Nature Engagement Design for the Web of Life, systematically presenting his thoughts and practices in recent years in design theory, international curation, and urban education practice. He proposed that in an era of overlapping crises and highly interconnected systems, design should move from “designing for people” to “designing for the web of life”, and shift from localized fixes toward regulating and restructuring for overall “balancing dynamics”. This shift is key to activating the “endless vitality” of a city, and even an entire civilization.

From “Design for People” to “Design for the Web of Life”

Lou Yongqi’s line of thinking originates from the World Design Cities Shanghai Manifesto (referred to as the Manifesto), released at the World Design Capital Conference in September 2025. During the drafting process of the Manifesto, the parties involved progressively advanced the discussion around the core principles of “design”: moving from the traditional “human-centered” approach, to “humanity-centered”, and further to “Human-Nature Engagement Design for the Web of Life”. This evolution reflects a clear recognition, that in a highly interconnected global era, design has long transcended its role as a mere accessory to product aesthetics and is now emerging as a key productive force reshaping industrial chains, resource utilization patterns, and social structures.

It is precisely for this reason that the “problem awareness” of design needs to be redefined. In the past, it was often understood as “how to make products more user-friendly” or “how to make things more popular”. Today, the questions are gradually shifting to “Is the way humans exist on Earth sustainable?” and “Are our systems and spatial arrangements continually amplifying inequality?” This signifies that design must now address not only localized experiences and short-term efficiency but also deep-seated structures related to ecological carrying capacity, intergenerational justice, and social stability.

Hence, the perspective of the “web of life” is proposed: the world is viewed as a fluid and complex network system where forests, rivers, cities, infrastructure, and humanity itself together form an evolving whole. Humans are an important node within this network but are no longer the sole center. Design no longer starts merely from the “user” but seeks to reshape more balanced and sustainable relationships among different species, regions, and social groups.

This shift is, in essence, a “discipline of coordination”. It requires building new bridges between ecology and economy, local needs and global systems, immediate interests and long-term survival. In this process, the role of design is no longer that of a mere creator of objects, but rather a “weaver of relationships” and a “systems adjuster”.

Finding “Balancing Dynamics” within the Cracks of “Inequality”

The Milan Triennale Exhibition offers a clear case study of how the “discipline of coordination” can be put into practice. The 24th Milan Triennale Exhibition held in May 2025, took “Inequalities” as its overarching theme, challenging participating nations to directly address the fissures in contemporary society. For the Chinese exhibition area, curated by Lou Yongqi, the focus moved beyond a straightforward display of wealth gaps or regional disparities. Instead, it placed “inequality” within the vast timeframe of civilizational evolution, proposing the thought-provoking theme “Balancing Dynamics - The Law of Civilizational Development”.

From this perspective, equality and inequality, balance and imbalance, are no longer simply seen as “good” or “bad” opposites. Instead, they are viewed as recurring states of tension within the progression of civilization. History has never been a smooth straight line but is more like the accumulation of countless waves: rising, falling, and rising again. What truly matters is not whether these tensions exist, but whether they can be transformed into a “potential for change” that drives structural shifts.

Drawing on Laozi’s idea that “Reversal is the movement of the Dao” and the concept from Lunheng (90 AD) that “Harmony and opposition interact to generate change”, Lou Yongqi emphasizes that the Dao is not found in a state of stable destination, but in the continuous flow of unity between opposites. Applied to today, this means inequality must not only be acknowledged but can also serve as a source of leverage for adjusting our systems and spatial arrangements.

Guided by this understanding, the curatorial team worked with faculty and students from institutions like Tongji University, China Academy of Art, Tsinghua University, East China Normal University, and Southern University of Science and Technology to divide the exhibition into five theme sections: Web of Life, Big Food, Diverse Aging, Spatial Growth, and Regulating Balance, which, while seemingly distinct, form an interconnected narrative. Together, they demonstrate how inequality is woven into the fabric of everyday existence, from food systems and aging populations to urban structures and governance.

The exhibition design itself reflected the “Balancing Dynamics” concept. The entrance featured an undulating mountain form and a circulating water system, creating an abstract “mountain-water” landscape that suggested our relationship with nature can be rewoven. The Big Food section used stories about diet, logistics, and land use to show the global systems connected to a single bite of food; Diverse Aging placed the daily lives of older adults at the narrative center, prompting viewers to rethink what “growing old” means.

In this way, “inequality” was broken down into tangible, specific issues: which lands are over-exploited, who is being pushed out of city centers, and which people are excluded from digital systems. The task of design, therefore, shifts from abstractly “opposing inequality” to proposing new institutional and spatial solutions within these specific gaps. The goal is to introduce flexibility and redirect systems that are tending toward rigid, entrenched structures of imbalance.

Endless Vitality: From Linear Consumption to Ecological Nesting

If the Milan Triennale Exhibition revolved around the social dimension of “inequality”, the World Design Capital Conference held the same year in Shanghai focused more intently on the ecological dimension. The conference adopted the annual theme “Design Without Boundaries, Endless Vitality”. Here, “Vitality” is not merely an abstract cultural phrase but is endowed with multiple layers of meaning.

Firstly, it represents a new ethical perspective. Sustainable development is not just a technical issue but a choice concerning values, involving how production is organized, how life is arranged, and how ecology is placed at the heart of decision-making. From this viewpoint, “ecology”, “production”, and “living” are not three separate spheres but form an integrated whole that must be considered synergistically.

Simultaneously, “Vitality” also signifies a new set of pathways and relationships. Through archives, case studies, and spatial installations, the exhibition laid bare the detours and explorations humanity has undertaken in facing the environmental crisis. On one hand, it revealed the costs of the “Linear Economy”: resources are extracted, consumed, and rapidly discarded. On the other hand, it presented various efforts to “break out of the straight line”, such as material recycling, “Product-as-a-Service” models, and regional industrial networks.

Furthermore, “Vitality” points towards a new source of dynamism. Faced with the massive environmental debt left by industrial civilization, relying solely on efficiency gains is far from sufficient. It is only through design-driven institutional innovation and the reshaping of lifestyles that we can gradually restore soil, water, and air, creating space for new forms of civilization to emerge.

In the exhibition, these abstract ideas were translated into tangible experiences. The track beneath visitors’ feet, paved with granules from recycled sneakers, is a testament to Lou Yongqi’s Sustainable Campus design concept from over a decade ago. It stands as a tangible reminder that environmental protection is not a distant slogan; it can be practiced in everyday choices, like giving an old pair of shoes or a section of pavement a new life, integrating everyday objects into a circular system. Meanwhile, the art installation car at the entrance, assembled from a large quantity of waste plastics, visually articulated the tension between “speed”, “championship”, and “waste”.

Through such spatial orchestration, the transition “from linear consumption to circular symbiosis, from spatial occupation to ecological nesting, and from technological application to systemic restoration” moved beyond concepts and appeals. It was transformed into a verifiable, actionable roadmap. As visitors moved through the exhibition, they were not only reflecting on how humanity arrived at its present state but were also guided to contemplate the next step: how can cities become more sustainable and collaborative?

SUES as an “Open-Source Plugin”: Embedding Innovation along Shanghai’s Suzhou Creek

Shifting the focus from international exhibitions back to Shanghai, the conversation naturally turns to how the city is putting the concepts of the “web of life” and “endless vitality” into practice. On this point, Lou Yongqi specifically highlighted SUES, where he serves as president and which recently underwent a strategic repositioning.

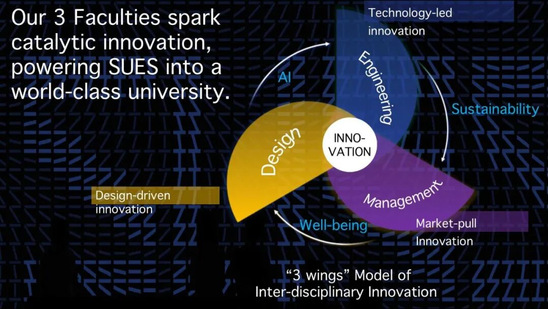

In 2025, the Shanghai municipal government officially designated SUES as a world-class application-innovation-oriented university with distinct industrial features. Engineering, management, and design, the 3 wings have emerged as the three key driving forces refined throughout the SUES’ decades of growth. Lou Yongqi’s mission is to integrate its three long-established strengths—Engineering, Management, and Design—onto a single drive shaft. This synergy allows them to function as a unified engine for innovation, powering the next wave of industrial transformation.

The banks of Suzhou Creek, particularly the area around the former Shanghai General Chamber of Commerce in Jing’an District, provide an ideal testing ground for SUES vision. Once a hub of trade and manufacturing, Qipu Road - a street that once defined a generation of urban fashion, the area is now undergoing multiple transitions: the integration of online and offline retail, the rise of new brands, and the reorganization of neighborhood functions. Within the “Open Waterfront” framework, this zone is being repositioned as an “open interface” capable of layering education, technology, industry, and culture.

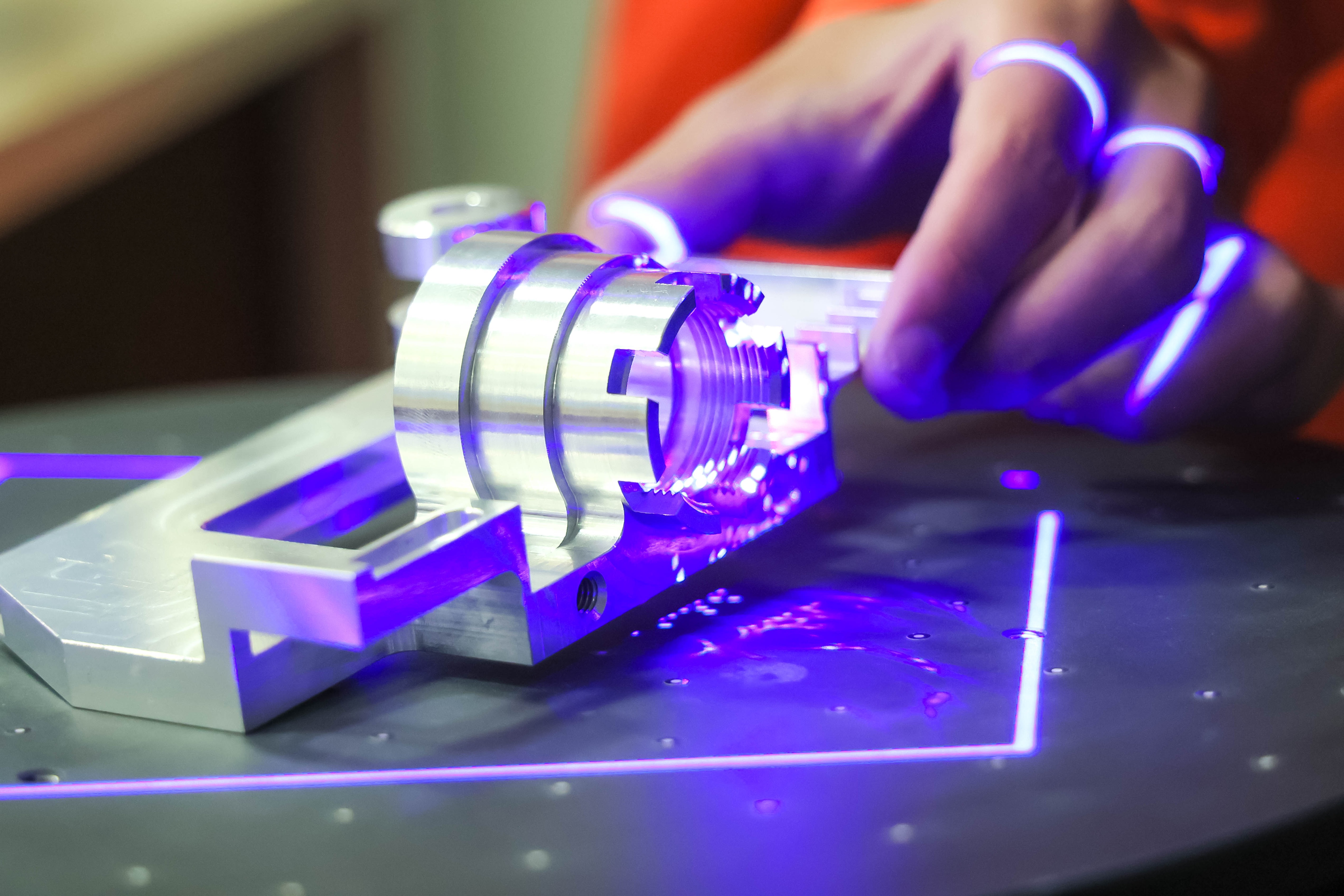

The planned New Fashion School embodies this vision of an open interface. It is not a traditional school or a single teaching base, but a global open innovation platform. It will bring together wearable technology, digital fabrication, new materials, interactive media, cultural IP incubation, neural sensing, and virtual civilization. Historic buildings will be revitalized into mixed-use spaces combining labs, workshops, and exhibition areas, attracting designers, engineers, entrepreneurs, and students to collaborate on projects under one roof.

On an urban scale, this platform functions like an “open-source innovation plugin” embedded into the waterfront. It transforms Suzhou Creek from a mere scenic belt into a live setting for knowledge flow, creative exchange, and industry-academia-research translation. It also relocates SUES from an enclosed campus to the city center, integrating it as a node in the daily experience of the public.

As education returns to the waterfront, and as research and industry reorganize at the neighborhood scale, the “web of life” expands from its natural dimension into the social fabric of the city, pointing to new forms of connection between people and between institutions. What is emerging along Suzhou Creek is a new relationship in which education, technology, and the city nest within and grow alongside one another.

The Direction of Our Water: From Potential to Kinetic Energy

In the concluding part of his speech, Lou Yongqi returned to the context of Our Water Season II. He suggested that the flow of water is not merely a natural phenomenon, but also a reminder: any system that stagnates will accumulate problems. Only by seeking new balance through movement and releasing pent-up energy through tension can we create space for the future. Suzhou Creek serves as a symbol of this—it carries the city’s history while simultaneously pushing new stories forward.

In this sense, “Human-Nature Engagement Design for the Web of Life” is not just a concept for design educators, but a thinking tool applicable to urban and regional development. It reminds us that when confronting inequality, ecological crises, and industrial transformation, we should not focus solely on immediate metrics or short-term gains. Instead, we must seek answers from a longer time scale, a broader spatial scope, and a more complex network of relationships.

As Suzhou Creek flows eastward to meet the Huangpu River and eventually the sea, the crucial question may not be where the water ultimately ends up, but whether the cities and communities along its banks have learned to translate the creek’s relentless flow into their own logic of action: transforming latent potential into sustained kinetic energy, and turning the waterfront before them into a civilizational interface facing the future.